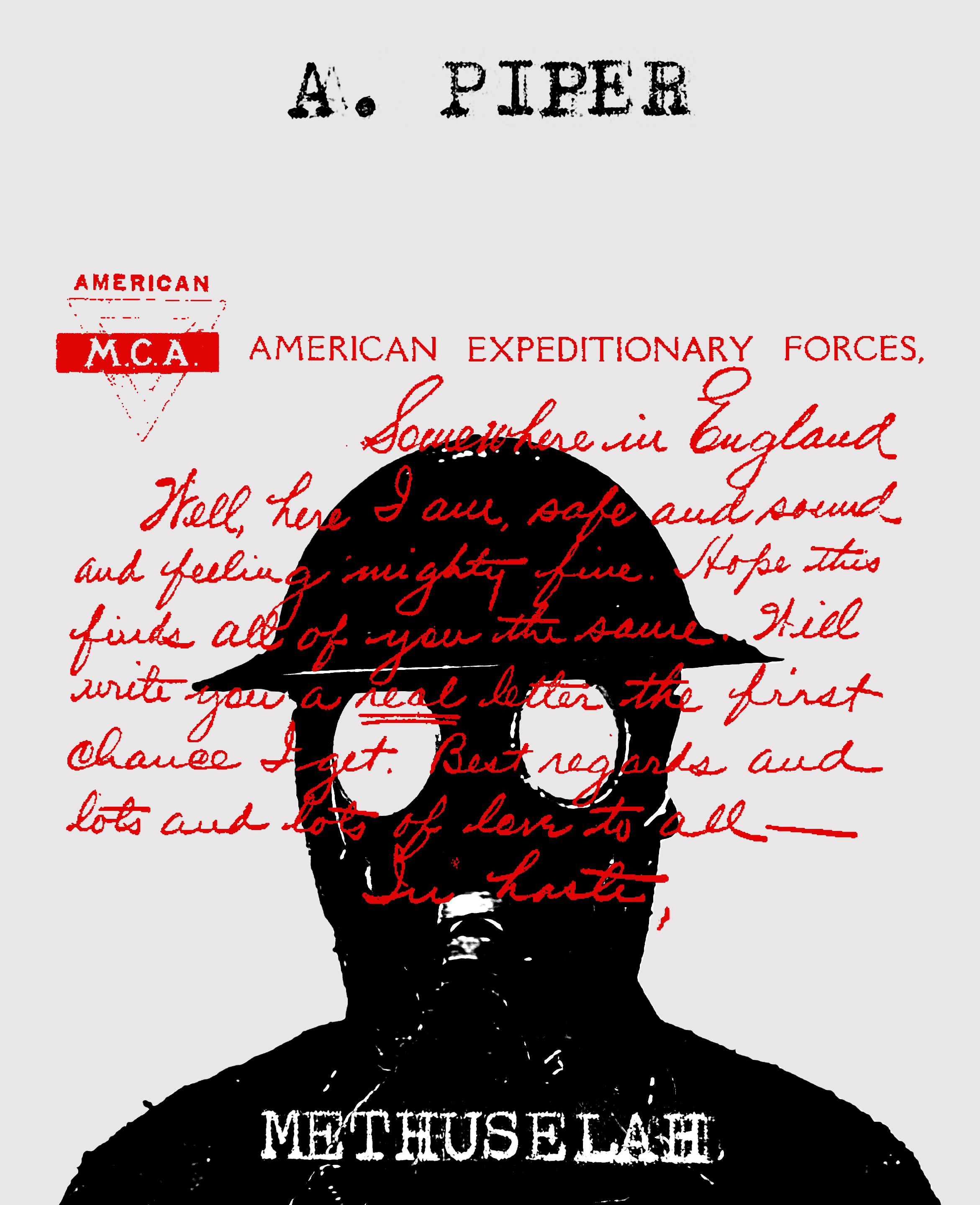

METHUSELAH - Chapter III - "Descent"

November 9th, 1951.

Samuel threw his fork down in surrender. “What, this again? This bullshit again? You know something, I go to work all fucking day for you, and —”

“Don’t lie to me. Don’t you lie to me. It’s that whore of a secretary, that —”

When did her tears begin to anger me, Samuel’s heart asked. When the face they fell upon went old and sour, it answered.

He wiped his mouth with the napkin and threw it to the floor. “Yeah. Happy fucking Birthday to me, right? Happy Birthday, Samuel. Wahh, wahh, I don’t trust you.” The mimicry drew heavy sobs from Victoria. He had enough of her and walked away.

“I … I hate you.”

I hate you. He was halfway down the hall, but he heard her. She wanted to be heard.

He stomped back, cursing under his breath.

“You think I asked for this? You fucking think, you …” The wrath boiled over. With a wild arm, a wooden chair was thrown across the kitchen. It crashed into the dishwasher and dented the stainless-steel paneling. The table went next, and the ice-cream cake Victoria spent two hours making fell onto her lap, making a mess of her dress.

The sobs were countless. “Y…y-you … you —”

“What?” The stranger’s face, furious but blank, was an inch away from hers. “WHAT? Spit it out!”

Victoria couldn’t speak.

“Fine. You know what? Fuck it. Fine. I do want her. Every day. Every day and every night and every time you bitch and moan about how lucky I am because your hair is grey and falling out and fucking tattered and mine fucking isn’t.”

Wielding a shard of dignity that wasn’t crushed in the pile of splintered wood and shattered glass, Victoria shot upwards from her chair.

“Yeah? Then why don’t you go and —”

“Already did.” A damned lie.

No tears, no words from her quivering mouth.

Samuel’s anger swelled.

“I never asked for this, Victoria. I never did. I should be dead, and instead I get a front-row fuckin’ seat to watching you fall apart and I just have to fucking take it in stride. I’m expected to watch it all just … just fade away and be a happy-go-lucky fuckin’ idiot, right? You think that’s good enough for me? Is this what I fucking deserve? You get the easy hand, the husband who never gets old and can work, work, work and always look young and spread your legs all night and I’m supposed to just shut up and accept it.”

“…”

The mocking continued. “Shut up and go to work, Samuel. Shut up. Nobody wants to hear it.”

“…”

“Yeah. Yeah. I know. It’s better you don’t talk.” His shoes were already on and he made for his jacket hanging on the hook.

“Where are —”

“Don’t know. Probably Adriana’s again. Wouldn’t that make you happy?”

“Samuel —”

“Maybe you’d like to watch.”

“You piece of —”

“Victoria, shut your stupid fucking mouth.”

The lady had enough. She stomped towards her husband and struck his face with all the might she could muster.

He struck back. She fell backwards.

Samuel would’ve killed him, had he been there. But her husband returned only after he saw his wife crumpled on the floor, a frail creature left to fend against forces she couldn’t understand.

He fell beside her, whimpering in agony. Victoria wailed louder, louder. Like a child he took her in his arms, and they wept like children under a never-setting sun that burned them in its light.

Away. Not gone.

He ate a bullet in July of 1979. A 12-gauge slug in October of ’81, a martini of carbon monoxide a month later.

It never worked.

He always returned when nobody was watching, like a thief in the night.

One day, during a noteless month of a noteless year, he wandered the stacks of West Babylon Public Library. The usual crowds of children were in school and the library had been open only an hour; the silence was thick. With no care for the books, he meandered around the labyrinth of shelves, hands in his pockets, eyes squinting under the fluorescent lights that seemed to paint everything a sickly green. He couldn’t stand those lights; the world loved them. An old man turned into the aisle Samuel was haunting, and, feeling a yawn rising from his throat, he covered his mouth and turned his head to the left, and his eyes landed on the spine of a dusty book with a peculiar title. An Index of Esoterica, Volume II, by Manly P. Hall. You know, the library is renting out more and more of that hippie-dippie crap, mentioned Joanie, Victoria’s younger friend, the week before. It’s horrendous. Nonetheless his curiosity took over. He snatched it from the shelf, dropping it in the process, and it unraveled on its way to the floor, landing pages-down. He muttered something, picked it up, and glanced at the left-hand page: it was a short entry on hypnagogia, the state of consciousness between sleep and wakefulness. Not much was written, other than a few scientific facts mixed with pseudo-metaphysical wordsoup, but a previous borrower had scribbled poetry beneath the entry — a clever bit of marginalia that, for one reason or another, stuck with the otherwise unread man.

Not here nor there;

away, not gone;

betwixt the neverwhere

and all that I’ve forgone —

Betwixt. An ethereal thing — more than a word: a playful image of tranquil nonexistence, an aimless man down at the lake who questions not his missing reflection in the water. He throws a pebble, maybe, or a bottlecap, or a coin minted two millennia before, or four millennia thereafter, and the ripples in the water go on forever. Betwixt. The word clawed into Samuel’s brain. On the drive home it echoed in his mind — a mantra without purpose, a shape in the mist.

No clear purpose — until his first attempt. July 5th, 1979. Her youth vanished and he didn’t quite like her at all, but he loved Victoria. The older gentleman who talked her ears off at the July 4th barbecue the night before — some doughy, lazy-eye’d Aragonese from the old country — gifted her a lightness she hadn’t felt in years. I should be happy, too, he heard in his racing mind. Samuel Carmichael, young forever. Heroes and dictators and demigods of mythic times salivated at the mere dream of immortality. Why didn’t Samuel? Any man — just about all men of red blood — would scheme for greatness after seeing that nothing, or nobody, could hurt them. Power moves and investments and the grandest of plans would be hatched and by the end of the week, there’d be an Emperor of the Earth hiding amongst the crowds, waiting for his moment. Time would be all he’d need, and have. But not Samuel — eternity was an enemy. He was reared in Pittsburgh when the Age was Gilded and the churches and cathedrals had the most ornate crosses on which the Son of David was crucified, and maybe it stuck with him that proper men die; only warlords of the steppes and cities dream of perversions like permanence. No Gilgamesh was Samuel. No ambitious Khan was he. No Patton, Carnegie, Xerxes, Napoleon. But he wasn’t stupid. Feigned it, maybe, or was handicapped — by whom? — during the death-carnival of that day, the War —

… that mass-sacrifice, the cavalcade of necrosis, that —

Away. Not gone.

July 9th, 1979. Thursday morning. Rain soaked everything. The tomato plants were green as ever and that brought a small pride to Victoria. She had a funeral mass to attend later that day, at the Church of St. Patrick down the highway. Someone died. Samuel forgot who. He didn’t pay attention to her. She shut the screen door carefully. Left the house without a word. He heard the car’s engine hum down the street, and he left the house some minutes later. He didn’t bother closing the door, locking anything. With a smile he climbed into his own car and rolled on with a pistol in his jeans and found a comfortable clearing in a thicket of trees along the Southern State Parkway and killed the engine and touched the barrel of the gun to the roof of his mouth and pulled the trigger and for a second he was at peace but the swirls came and he forgot who he was and what he was and what is was until there was the fire, a fire that men — clothed in whimsy — danced around and their eyes were like sharpened obsidian and their hands like burning embers and the sky a dance of gold and blue and the deepest vermillion man cannot quite comprehend, and when he looked upon the celestial judgment emanating from its perpetual beauty he felt its sorrow, its wrath, the furnace of an unquenchable wrath, but behind it, pardon — a looking to the other way, a pity, a —

Where am I?

Away, not gone, it said.

It pulled him up, up above the dancing devils, above that scorched plane, and he awoke. The rear-view mirror was fogged up. He recognized the man. Sergeant Samuel Carmichael, born November 9th, 1892. His breath was shallow as if he was sprinting down the trenches once more. Gas! Gas! Gas! The low fuel indicator shone red as he turned the engine over. He caught his breath. Just a dream. His eyes shut and he reclined in the driver’s seat. Rusty water dripped on his forehead. He opened his eyes and screamed at the clouds of blood splattered above him. The sun shone through the bullet hole in the roof. No escape. Again and again he struck the wheel, the radio, anything. He struck himself. Sounds left his throat — nothing recognizable as human speech. Banged his head on, then through, the driver side window. Madness. In tears and blood he treaded until the waves of violence calmed and disbelief suffocated the agony. How? He stared at the hole in the ceiling, the silver-white light of an overcast sky pouring through. How? I … I died. It wasn’t fair. An hour passed before he could regain his composure and get back onto the highway, but ten seconds of driving saw the engine sputter and choke as the fuel tank ran dry. He was able to pull over, but there were no cellphones in those days. He walked in the rain to the nearest exit, 36S, to Straight Path, a long road in West Babylon. There was a gas station a few minutes’ walk from the exit and the old Egyptian man, Hosni, was kind enough to let Samuel use the phone. I was in a bad wreck up the street, lied Samuel. The other guy sped away. The blood on Samuel’s t-shirt made Hosni woozy. No, I’m not hurt. I’m fine. Samuel dialed his wife and gave her the gas station’s address. She hung up without a word. He was just glad she knew how to use a map. It took her over an hour to get there, and when Victoria saw her husband covered in blood and broken bits of a center console, she was silent. Emotionless. She didn’t ask any questions. No surprise or grimace found her face and they drove back home to Islip without a word. She hadn’t looked at him until they pulled into their driveway, but when she did, she saw him weeping, and it was so very much unlike the man to cry. His act was over — the curtains closed and the lime lights dimmed and he crumpled into himself as he cried. She laid her wrinkled hand on his head, his back, and then her head on his shoulder.

Where was that place?

Where did those moments go?

What is a sliver of eternity? A division so small, it’s meaningless — so meaningless, it may have never happened, but Samuel knew he was somewhere, somewhere with weight, somewhere meaningful.

Days later, he opened up to her about the dream — the place, the Betwixt. A silent terror gripped her heart. Victoria recommended the free counsel of Father Hughes, one of the, in her words, few faithful priests in the diocese. Samuel laughed at the notion. Faithful priests? So there’s faithless priests? Why live that horrible life if there’s no faith in it? He delved no deeper into that question and couldn’t stand Victoria’s god-nonsense anyways. It’s all crap, Vic. What’s he going to tell me?

Samuel, that place you saw, that’s —

Look, I don’t want to hear it.

He fossilized in his chair and disappeared into the reflection of the television’s screen. Hours, days, weeks would pass there. One year, two years. Victoria aged. She prayed and lit candles and had masses said in her husband’s name and grew lighter in spirit, and with that, she found the strength to take a step back from her beloved’s maladies. The mystery of his pain and place on this earth became clear only as she stared at the clouds in prayer.

… Two whole years passed. Two years of lazing around and not going to work and numbing the pain with drink and sometimes Adriana, and another young Stacey that Samuel only met two or three times. The man sparred with guilt when he found himself waiting for his elderly wife to die, though he knew there’d be nothing left once she’d be gone. One overcast day, an afternoon fog embraced the town. The temperature was perfect – 59 degrees Fahrenheit – and he felt tranquil, more or less, for the first time in almost a decade. He figured a walk would be nice, to see the new cars of the year drive up and down the street — Man, that’s an ugly one — and the mist painted a dream out of everything. The houses lining the roads looked older, more dignified. Behind the clouds, the sun’s disk played, a lightbulb over the crown of everyone’s head. After an hour or so of walking, Samuel’s spirits remained unusually high, and the idea that he should’ve been spending more time outdoors, in nature, took to him. When he returned to the house, Victoria was waiting for him, knitting a pair of mittens on the couch.

“Were you out for a walk?”

“I was,” he said.

He looked at her, sighed, and smiled. She set the needles down on her lap.

“Are you unwell?”

He laughed. At once the lightbulbs in the house danced and Victoria’s heart sang.

“No. Not unwell. I didn’t mean to disturb you.”

“Samuel.”

“Yeah?”

“Sit with me.”

He started on as if she didn’t say a word. “I’m going to buy a tent.”

“A tent?”

“Yes. And the whole works. A whole lot of camping gear.”

“What brought this?”

“The green, the foliage.”

“… the green?.”

“Greenery. Nature. I just … well, I just need it.”

“Sit with me.”

“Where’s that sportman’s store? What’s it called? Lodell’s?”

“I don’t know.” She sighed. In surrender, she held the needles loosely and continued to knit.

“I’m heading there in a minute.”

“You don’t know where it is.”

“I think it’s in Sayville,” Samuel said. “Or thereabout.”

He disappeared into the bedroom. Having caught his breath, he stepped back out and lingered at the edge of the hallway, staring at his wife.

She looked up and caught his gaze.

“Hi, Vic.” His eyes carried an apology he didn’t know how to voice.

She knew he was doing more than his best in that moment, and she smiled.

“Hi, Sam.”

Even at that age, she wanted all of her husband to herself. She was careful, though, not to smother the flame that awoke his poor heart. Every bit of her wanted to tag along on his little adventure to Lodell’s, and it took just as much of her to not impose. She remained knitting as shoes flew onto his feet, and his feet out the door all the same, and when the living-room was silent again, save for the wood wall-paneling that groaned in the autumn days, she stared into a portrait of the Nazarene, and, tearing up, she spoke. Lord, what is happening? What are you doing with my Samuel? When will the craziness end?

By the end of the week, Samuel had his tent, his pack, his knick-knacks, tools and toiletries, plus a stack of hiking magazines. A shotgun, too, with a fine wooden stock, sturdy and solid. Ed, the store manager, hadn’t any shells left, so Samuel entertained himself by dry-firing the shotgun, pumping and shooting just to hear the click. He grinned every time. On the evening of October 27th, 1981, after finding the shells elsewhere, he broke the news to Victoria at dinner that he'd be gone for a few days.

“… Are you sure, Samuel?”

“Am I sure? Yes, I’m sure. I’m thinking upstate. The Adirondacks, one of the parks up there.”

“OK.” She sipped her tea and watched a young family pass the house on the sidewalk. “OK.”

“What is it?”

“I think you need this.” She forced her gripes and complaints back down into her diaphragm.

“Victoria.”

“Hmm?”

“I’ll be fine.”

“I know.”

“Nothing can happen to — ”

“You don’t know that.”

“I don’t?” He raised his voice. “I don’t?”

“No, you don’t.”

The new joy he found ran sour. Without a word he rose from the table, tossed his dish into the sink, and continued to pack. The Adirondacks called him, and he wanted to know why.

One week, he told himself. One week to get his head right and return a better man, or at least, a more present man. If not for himself, then for Victoria.

He wasn’t supposed to leave for another six days, but the car was already packed. Victoria was out with friends. It’s cleaner this way, he thought. The note he left on the table was written with little consideration for his loyal wife: brief chickenscratch in his signature all-capitals print.

DECIDED TO LEAVE RIGHT NOW. BE BACK SOON.

S.

Victoria read the note with a sigh. Her stomach sank. She folded it neatly and held it in her hand, thumbing the paper’s edges with a hopeful tenderness. The moment would be passed sitting in solitude, one leg crossed over the other, as she lit a cigarette and wondered what either of them had done to be given a cross most arcane, as Father Hughes had put it. Quickly the sun was setting, and she spoke to the lonesome cloud on the horizon, asking it if there really was anything up there.

Samuel saw that very sunset from behind the steering wheel as he crossed the Whitestone Bridge. Shards of sunlight flickered across the bay.

… No Gilgamesh was he. He saw not the deep. But it saw him, and like a voice crying out in the wilderness, it whispered his name and drew him near, and he never noticed that it was the voice he followed. A thought that he shouldn’t be traveling at night came and passed. The night can’t hurt me. Nothing can, I think — a dangerous supposition. Night fell. He was northbound on I-87, passing Newburgh, Poughkeepsie, Coxsackie; when Albany was in his rear-view mirror, he was as far north as he had ever gone in the United States. A sign for Arthur Motel appeared on his right and he took the exit. Doris was the concierge of all six rooms. Hers was a rusty sadness and she’d spill over the top to just about anybody who’d listen, but Samuel just wanted to close his eyes and open them when the sun and the mountains were in view. He nodded along to her story of how her dog had died from a kidney infection that ran up a fifty-dollar vet bill, and he found a fine gap between her words to say that he’d like to stay and chat but he wasn’t feeling well. The bed squeaked and a fly pestered him in the dark but after a half-hour he dropped into sleep and woke up somewhere north of five o’clock. He hit the road again. Still some hours passed but soon enough, approaching from the south, he was there: Dix Mountain Wilderness Area.

He pulled over, putting the engine to sleep.

Alone. No Victoria, no Suffolk County. No ugly modern motorcars that all looked like electric clippers. No recliner that melded to his form and grew matted hair and a hunch in its back, no flickering ceiling-fan bulbs he couldn’t be bothered to replace, no television whining on about the luxurious death of the world.

Nobody to say his name.

His pack was already set. He slung it around his shoulders. The shotgun was tied to it, as were the tentpoles and canvas. He crossed the road, and approaching the tree line, he stopped to look back at the car one more time. There was no concern for its safety. Left. Right. Left. He marched straight into the woods.

Nothing. No exploding shells. No clamoring Beatles. No loud arguments about milk or eggs or he-said-she-said from the next door neighbors. No braindead talk of MTV or Pac-Man or nuclear warheads nobody had the gumption to launch.

No despair. No anguish.

Clarity.

Samuel heard himself. Samuel was himself. He was his arms and his legs and his feet and his torso and he wasn’t just a tired stream of vision looking out from two bony windows cut into his skull. He found is and he laughed and teared up a bit, and then he sprinted, as fast as he could, jumping over logs and creeks and rejoicing in the novelty. He paused to catch his breath and when he did, he looked all around him, and didn’t know where he was. No map. None at all. Lost, as always. He walked in one direction for a while to see where the fallen leaves would lead him and he happened upon the Round Pond Trail. Novelty wears away. Those highlands were a trap. The light he hoped to find there sandbagged the sergeant. The emptiness returned. He shambled on away from the trail and tripped sometimes and his soul smoldered in quiet rage and the soil was vengeful dust. The trees and grasses refused to answer the question of his condition but still the mountain beckoned. The snow fell and the ascent was steep. Where was the final rest? Where were the ashes-to-ashes and dust-to-dust wander off to? The birthright of death was a treasure of great value but he was the bastard child of lesser royals exiled for petty rebellion. Forever. He’d live to see the mountain erode and share its memory the thousandth generation after his, and they’d die and so would their children and he’d forever be the man on the mountain, a beast from an era shrouded in obscure myth, a myth of myths, the desert-soul, thirsty for millennia, waiting, waiting, stretching forward and backwards into time, forbidden from —

— a voice from the mountain — Samuel, it called. It echoed in the imagination’s corner that is more real than wakefulness. He heard not the letter nor the word nor the flowering of life that proceedeth from the word but still the man knew his own name and something, somewhere, on a corner of that harsh iroquois earth, his name was uttered with the authority of skies and seas and —

Samuel.

He no longer climbed. He marched, marched up the rocky ascent, knuckles white, frantic and furious, ready to —

Samuel.

“WHAT! LEAVE ME ALONE! WHO — WHERE ARE YOU? WHERE ARE YOU, DAMNIT! LEAVE ME ALONE!” He climbed and climbed and screamed to himself and tears fell and he gnashed his teeth at the humiliation from nowhere, from the invisible, from the cosmic house with red and blue stained windows where the fire was warm but there was no entry, no entry, no door to knock on from out in the cold. “Who are you?” Without knowing the reason he sobbed. He sobbed more and angrily climbed the ascent. It stalked him, the Wind that knew his name, a gentle breeze that infuriates the waves and lashes at the canyons with an overseer’s whip. What next. What next. No escape. What next.

— Samuel.

Out of breath he stopped and turned around, and the descent below was craggy and unstable. The snow became a storm that blotted out the sky and he crumpled into himself, and to the east, down the descent, he saw the very land point its finger at him, at him, at only him, and the trees and the ravens and the stalking-wolves all condemned him with a searing hopelessness that could cinderburn the leaves and rust the air and strip the very bark from the elder oaks who knew well the crier of Samuel’s name as they bowed in its presence; and, rising from their bows, they saw a man pause in their midst, sit with his knees close up to his chest, and cry a deep wounded cry. Like a child he rocked back and forth and hit himself and mumbled over and over that had no choice, blaming himself, shouting that he didn’t mean to, he didn’t mean to, and then cover his ears yelling at something to stop, to shut up, to stop, please stop, stop, I didn’t mean to, we had no choice, please stop, please stop, and the trees and squirrels and all the birds of prey begged him not to do it, but he reached for the shotgun strapped to his bag, loaded a slug, and, like the time before, pointed it into his mouth and up towards his head, and removing his boot and kicking it down the ascent, he pushed down on the trigger with his toe, and after a deafening roar and a gentle settling like being dropped onto a cloud of cotton from on high, he awoke to a tap on his shoulder. He picked up his head, and, looking around, he was seated on the wobbly bar stool of an old speakeasy — he knew the place, but couldn’t remember its name, let alone the ghastly carriage that took him there.

The bartender walked over. I know this man, Samuel whispered to himself. “Looking dapper, Pa.”

Indeed, it was his father. How long had it been? His face, like everyone else’s, was morose and without expression.

“Long time no see, son. Gin?”

“Yeah, warm.”

His father smiled a calm grin found in later years, and began to work on his son’s drink.

“Always liked this place.”

“You came here for your cousin’s wedding party, remember?”

“… That’s right — me and him, and the groomsman —”

“May 19th, 1912. You almost put man in the cemetary, boy oh boy … him and those crooked cards.”

“I ever tell you how that went down?”

“No. I was long gone by then, Sammy-boy.”

“Why’d you leave, Pa?”

“Murfreesboro. Then, Sioux City.”

“… No, not where. Why.”

A patron walked in — a young woman, dressed from a different time — the early Sixties, one could guess, by her bandana, long braided hair, and that awful tie-dye Samuel always hated. She looked around quickly. Groovy. She winked at the bartender and took her seat.

Samuel waited for an answer. Pa’s gaze tore away from the young woman with slow reluctance, and his eyes met his son’s; a most apologetic smile shed across his still-young face, and he mouthed I’m sorry, son. I never could resist. Far away the bartender felt as he gravitated to the young woman with eros in her eyes and flowers in her hair.

There was a newspaper to his right he didn’t notice before. The headline read:

THE DEVILS LAKE WORLD

DEVIL’S LAKE, NORTH DAKOTA — WEDNESDAY, APRIL 26, 1922

KILLS WIFE, SHOOTS BABIES, AND IS KILLED HIMSELF BY TRAIN:

JIM KALLIAS MURDERS HIS WIFE WHEN SHE REFUSES TO LIVE WITH HIM

That can’t be right, Samuel thought. This old bar — North Dakota? No, it’s far from there — where am I?

“Hey! Oh! Sarge! There he is!” An unseen face lit up and rejoiced at Samuel’s presence. A hand patted Samuel on the back. When the stranger took a seat on the stool, the sergeant looked over and was hit with surprise.

“… Is that you?”

“You bet!”

“… Randazzo. My God, you’re looking great, kid!” They were awkward as both couldn’t decide on whether a handshake or hug was more appropriate, but Samuel eased the moment by embracing the young man and hugging him tightly.

“Yeah. Yeah. Man, how are you, Sarge?”

“Sarge no more, Randy. And if I was,” Samuel spoke, wagging a finger then slapping him lightly on his right cheek, “I’d have you shaving that face over there in the water closet.”

The two laughed. “I suppose you’re right, Sarge. I suppose.”

“Where are your brothers? Those two troublemakers?” Samuel looked around and didn’t see them.

Corporal Randazzo frowned. “Didn’t make it.”

“None of you made it. All three … the damned shelling …”

“Didn’t make it here, Sarge.”

Somber, that tavern. Samuel noticed the copper ceiling tiles; they were ornate, with flowers and faces of animals at the corners. Life. The tiles’ reflection distorted his face — but only his, and the whole tavern, as seen through the tiles, was empty. He jerked his head back down, and the place was again full, bustling with activity – and there was Randazzo, smiling the grin he always wore when he was about to do something dangerous.

“Do you understand yet?” Randazzo’s grin ceased.

“I understand that there’s a wall of medals in your name. Kid, you were brave, braver than —”

Randazzo’s frown deepened. “Do you understand yet, Samuel?”

He was about to admit that, no, he didn’t understand a thing, but a barback walked through the swinging doors from the kitchen, and as they swung, someone’s screaming — desperate and hoarse — filled the bar. When the door swung back, Samuel caught a glimpse of the man who wailed as if hot irons were being pressed against his chest.

Gershonowitz.

— his beady eyes dead as steel mill slag, his pointed nose crooked and hooked, his cratered skin pockmarked with scabs and blackheads —

Samuel’s heart raced, sank to his stomach, and he slammed his fist on the bar. “What the hell is he doing here?”

“Purgation’s kitchen.”

“… Hell’s Kitchen? That old neighborhood — Yeah, that’s right. I remember — he’s from New York. Like you.”

Randazzo smiled; he knew the time for Samuel’s understanding would not be in that moment.

“… Let him rot.”

“What’s that?” Randazzo straightened on the stool.

Without notice, Samuel tossed his glass across the room. It shattered. Gin splashed everywhere. “Bring him out here! Get him, Pa! I’ll break his fucking neck. I’ll cut him open. I’ll split that fuckin’ skull of his, I’ll –”

“Easy, Sarge, you —”

Samuel grabbed the collar on Randazzo’s shirt and pushed him to the ground. Tears welled up in his eyes. “No! No! Shut up! Shut the FUCK up! He got men killed and LAUGHED about it! He got you KILLED, Randazzo! He wasted you and your brothers! He sent you to that … that fuckin’ machine gun nest for no reason and laughed about it and walked away! You remember! I know you do! You remember what he did, those … girls, those — who the hell are you looking at?” Samuel shouted at his father with a pointed hand. “You know what that man did? That rat kike? What? You think that — ”

“I’m going to call for the police,” Pa replied, cool and collected. The telephone he dashed for was a cordless set popular in the early 2000’s. He mumbled something into its receiver and hung it up with an electronic beep.

“I’m not going anywhere. Bring him out here. Bring that rat fuck out here, or … I’ll go back there and bring him out myself.”

“Where will you go?” Randazzo was entertained. Patting away the dust that clung to his trousers, he picked himself up and sat again beside Samuel.

Samuel was out of breath. He heaved, in and out. “I … I don’t know. But … he … he’s coming with me.”

“No, he —”

“Yes. Yes … he is.”

The tavern’s double doors flung open. In walked a man dressed like a New York City Police Department officer, 1980’s attire. The leather jacket and cap were a perfect fit.

“C’mon, big guy. Let’s go.”

“What? What did I do? Tell me. What the hell did I do?” He looked at Randazzo, then the bartender, then the other patrons in the bar. One caught his eye. He knew her from ten thousand miles away — the ice-blue eyes, the freckles. Marie.

“Marie —”

“C’mon. Let’s go,” the officer said. “We don’t have all day.” He turned Samuel around and, pulling his arms behind his back, fixed handcuffs to his wrists.

“Marie — Marie, I’ll be right back, I promise, I promise, OK? I didn’t see you there. I’m sorry … sis, I didn’t see you.” There was no trouble in her eyes. She smiled and waved.

The cop led Samuel away, to the open door. Beyond it was nothing but a white fog. “Where are we going, officer?”

“Away,” He laughed. “But not gone. You’re fine, big guy. Don’t worry.” Before stepping out into the fog, he felt a tug at his shirtsleeve. He turned and faced the man. It was his father, no longer wearing the bartender’s coat.

“Pa. I’m … sorry, I wanted to tell you the story about those guys — I roughed ‘em up good, you know, and — ”

His pa only frowned.

Samuel looked over his shoulder once more to the swinging doors of the kitchen — the screaming grew louder, more pained, troubled, vindictive — and, stepping through the doors, into the fog —

Samuel awoke covered in his own blood, shivering, in his car. Consciousness was regained but with difficulty, as if waking from a deep slumber, mouth parched and mind foggy. How … how did I get here? The vision he endured would’ve evaporated with his labored breaths had he not made a dire effort to hold onto it. It all came back to him: the walk, Lodell’s, the tent, the gun, the Adirondacks, the ascent, the presence, the suicide.

He whimpered.

No escape. No way back.

He tried to turn over the car’s engine. It sputtered and heaved but didn’t start. He tried again. And again. And again. Over and over. Stuck. It started with a groan. He thumbed through the map he had left behind, leaving thumbprints of blood on the pages. He made a U-turn and, fighting the grogginess, started to drive away.

No despair, no anguish. Just the sour emptiness of an old milk carton with a rotten odor.

I failed Victoria, he convinced himself.

She doesn’t deserve any of this.

He returned to Long Island without stopping. As their home on Vermillion Lane came into view, he noticed Victoria sitting on the wooden porch with her head in her hands. He honked the horn twice. Her head rose. When he killed the engine, he pushed open the door and was one foot out of the car when she rained slaps upon his face, over and over, angry and desperate. Samuel caught the old woman’s wrists. He didn’t shout. His temper didn’t boil. He witnessed her age and exasperation and was grateful she never left or went to the television news networks and still cooked his dinners, and tears fell from his eyes without sobs or drama or even much emotion.

“Vee. I’m sorry. I’m sorry.”

“Three … three weeks Samuel. Three. Almost a month. A month! You left me alone here. I was alone!”

“I — what are you talking about? It’s been, what, two days? Only two —”

“Damnit, Sam, don’t do that. Don’t —”

Her breathing eased. It was only after she calmed that she noticed the blood stains on his shirt, his pants, his everything.

He nodded.

“You said you wouldn’t. You promised. Samuel, you … you …”

She held her hand to her chest, and she collapsed.

“Shit! Victoria! C’mon! OK. Turn on your side — just like that — stay right here. Stay right here, sweet pea.” She nodded impishly. He sprinted inside and dialed for an ambulance, which seemed to take its time getting there, even though the firehouse was only blocks away. By the time they reached the hospital — also not far at all from the house — Victoria was fine. Her vitals were normal, considering her age. The doctor, a small, impatient Filipino with a wispy moustache, waved it off as anxiety and off they were, back to the house in Samuel’s blood-spattered car.

He would spend the rest of the day in silence. The day turned into a few, then a week. Before long, a month passed without Victoria acknowledging his presence. She’d always go cold and distant when working through something in her head, and there were times when Samuel was curious, but this time, he didn’t care much. She had Antoinette and Denise and Marilyn, all parishioners from that Church of hers, plus that Fr. Hughes — all friends her age, in her lane. Christmas came and went and the New Year crept in without anything resembling warmth from either half of the marriage, and the only thing on Samuel’s mind when that silly ball dropped in Manhattan at midnight of January 1st, 1982, was whether or not Victoria kept his condition a secret from the friends she seemed to spend most of her time with.

The next morning, he decided to break the silence with the question he was obsessing over.

“Vick.” He called to her calmly from the living-room couch.

She entered slowly.

He sighed. “Can I ask you something?”

She stared at him blankly.

“Look … I trust you, but — ”

“Nobody knows, Samuel.” She turned away.

And that was that.

He trashed the entire day on the couch. He stared, but at nothing — the wallpaper, the coffee table book of Canaletto’s art that Victoria had picked up for a bargain, the television screen. A breeze made the windchimes sing and that brought a kind of numbing comfort to Samuel, but he had enough. Prisoners who attempt escape are likely to try again. Maybe three time’s a charm. He doubted it. Victoria was on a parish retreat with friends of hers — something she dreaded all week but still attended, much to Samuel’s amusement — and this time, it wasn’t the despair, but plain curiosity.

The Betwixt beckoned. It was the one place where a modicum of meaning could be encountered. But the Betwixt was found only in the celestial alleyway full of burned-out oil drums of the homeless — no real way to get there besides going down to its gate via the violence of his own hand.

He sat up from the couch and eyed the door to the garage. There was enough time to try it again before Victoria returned. More than enough. He walked down and spied the door behind him. There was fresh weather stripping at the foot of the door that would block any carbon monoxide from leaking into the house. The garage door was heavy and formed a good enough seal on the concrete floor, so there’d be no escape of gasses through there, either. He looked around. Tiny garage. One car was always parked outside. For decades, this made the house a regrettable purchase, but in that moment, he felt lucky. Without hesitation he climbed into the car and brought the engine to life, reclined the chair, and relaxed. He smiled. The minor headache came after some time, then the major fatigue, then a painful sleep that fell upon him like vultures. Black. Aware, but an awareness of nothing. Not life, but not death. The door to the Betwixt approached, a heavy oaken portal dressed with adornments of silver and gold, and he tried to open it but it wouldn’t budge. He knocked, then pounded, then tried to kick it in, but nothing. He jogged about thirty feet away and sprinted back, and with all the momentum of his muscled frame he slammed into it hoping to knock it off its hinges and send him barreling into a place where he could receive a kind of message, or hint, or anything at all. Instead, it gave him a sore shoulder. He sat in exhaustion, catching his breath, and realized that there was no floor — nothing below him. The ground was black, as there was no ground. To his left, black; to his right, black. The door was the only visible thing in the dark foyer of the Betwixt. Wait a second. He shook his head and rose from the invisible floor. With ease, he walked around the door frame to the opposite side.

False entry. A portal to nowhere.

He sat down and fell asleep after some time, and awoke in the driver’s seat, choking in the toxic cloud he created. Throwing open the driver side door, Samuel tumbled out and vomited. He limped towards the garage door switch and pounded the ‘UP’ button. A rush of oxygen washed away the disappointment and the fresh air soothed his lungs. Like clockwork, Victoria arrived only minutes later. She didn’t know what happened. She hummed along the driveway and when she got close, Samuel interrupted whatever she was about to say and he told her that he had given up, that he’d talk to Father Hughes.

Victoria had prayed all day for this at the parish retreat. She hid the intense joy welling up from her tired heart.

Jack assigned a round-the-clock observation of Samuel’s stinking remains.

But someone was bound to crack.

Somebody would look away, or nod off for just a second or two, or be struck with foul indigestion, requiring an emergency visit to the bathroom.

Fr. Hughes floated around his office like the dust suspended in the rays of light pouring through the windows. There was a hobble in his step, but it slowed him none. He messed about with the papers that seemed to cover every surface of his desk, arranging and rearranging and disarranging the just-rearranged.

“I … ah, won’t you look at this mess … I entirely forgot about our meeting,” said Fr. Hughes, a permanent grin disobeying his annoyed eyes. “Oh — do you like Chopin?” He walked over to the record player.

“That’s fine.”

“On or off?”

“Whatever you want, Mr. Hughes.”

“You’re the guest.” His grin grew wider.

“On.”

“Well, I’ll keep the volume low. Very low — yes, that’s better.”

Samuel nodded.

Fr. Hughes plopped down into the leather chair facing Samuel from across the desk.

“Tea? Coffee?”

“No.”

“Well, then.” His eyebrows raised, waiting for his guest to start.

Nothing, awkwardly, then — “My w… Victoria wanted me to talk with you.”

“She’s still your wife, Mr. Carmichael.”

“Yeah. I get that. Look, how much do you know?”

“Everything.”

Samuel bit his tongue.

Father Hughes continued. “I’ve seen the photos. Your military record. The letters. Your birth certificate. That whole tin of memories.”

“That fuckin’ —”

Fr. Hughes’ hand slammed onto his desk. “You will mind your language here.”

The one thing holding Samuel back from bursting out of the chair and leaving was the promise he made to Victoria that he’d listen to what Fr Hughes had to say.

“First thing’s first”, Fr. Hughes started. “Your secret is secure. Only I know. None of her friends know.”

Samuel remained quiet.

“That’s a hard cross to carry,” Fr. Hughes continued. “I hope you’re appreciative.”

“I guess so.”

“You guess so.”

“That’s what I said. Victoria gave me the nonsense about the weight of crosses, how the heavy ones are reserved for the … it doesn’t matter. It’s all fakery, I think.”

“You think?”

“That’s what I said, right?”

“But you aren’t convinced.”

“No. Almost. But … God? What I’ve witnessed … no. Don’t think so.”

“I understand your fear.”

“Fear?”

“Poked and prodded like a lab rat. Hence the secret.”

“That was decades ago, the … the obsession with keeping it a secret. Twenty-five years or so. I still do everything I can to keep the secret but it’s not just that.”

“What is it then?”

Samuel shrugged.

“Not shame?”

“No. Why — what do I have to be ashamed of?”

“I don’t know, Samuel. I’m only asking.”

“I — I don’t know. Look, I — I’m here, really, because Victoria wanted me here. I, you know, after …”

“Yes. I know. That wasn’t your first time?”

“Which one?”

“Well, that answers that, doesn’t it?” Fr. Hughes smiled when Samuel’s grin broke through the stony seriousness. “There’s no need to be so serious here. Or out there. Or anywhere you go, really.”

“Whatever you say. No, it wasn’t my first time. Actually … there were three times. The car was the third time. I was, uh … experimenting.”

“What’s that? Experimenting?”

“I … first two times. It was … bizarre. When I was, I don’t know, dead … there were dreams. Dreams like I’ve never had. Very real. As real as us being here, at least.”

“Do you remember them?”

Samuel thought hard for a second. “Not so much the first one. The second one, only a little. I’ve written them down. Victoria helped with that. I should’ve brought them, maybe.”

“What do you remember from the second one?”

“Gee, I … well. I was in an old bar, like a speakeasy. Remember? The — oh, I — you probably weren’t old enough.”

“Not at all. I was born in ’21.”

“Twenty-one … I …”

“I know. I’m just a baby in your eyes, right? Long time ago. Well, that dream — what do you remember?”

“1921 … you ever find the world so damn ugly these days?”

The father laughed. “Wicked and grim. We’ve seen nothing yet, I’m afraid. But go on, if you will — the dream.”

“Oh — sure — I was in that bar. And there were people there, people I haven’t seen … my father was the bartender. Randazzo, from the war — an Italian fellow — was asking me … it’s a bit foggy, the memory. I’ve been very tired. But he was asking me, I think, if … I understood something.”

“You don’t remember?”

“No. I think … if I understood why I was there.”

“Hmm.” Fr. Hughes was silent in his deliberations.

“The third dream — well, I was —”

“And this is after you … experimented with the car in the garage.”

“Right.”

“Go on.”

“Well, I was in this black … place. Pitch black, except for a door. It was a pretty door, the kind you’d see, I don’t know, fifty years ago. Saw a lot of doors like that in Europe, in Paris. Fine metalwork. You understand it.”

“Of course.”

“I tried to open it. Tried a few different tricks. Slamming into it. Jiggling the doorknob. It wouldn’t budge an inch.”

“What did the door lead to?”

“I can’t know.”

“What do you think it lead to?”

Even the idea of sharing the name made Samuel cringe, but nonetheless, he continued. “I call the place the … uh, the Betwixt.”

“The Betwixt,” Fr. Hughes repeated with raised eyebrows. He was amused.

“Yeah, I was reading a book down at the library a few years ago. Someone wrote a poem, I guess, onto the margin of a page … I think it was a poem. I don’t remember all of it or what it was about, but whoever wrote it used the word ‘betwixt’. It means, you know, between.”

“Right. This place – why’d you name it the Betwixt?”

“Because,” Samuel explained, “When you’re there, you aren’t dead, but you aren’t alive. You aren’t awake, but you’re certainly not asleep.”

Fr. Hughes was quiet for some time. Finally, he spoke. “How interesting.”

“How — that’s it?” Samuel was expecting something — he didn’t know what — but the failed expectations were present in his annoyed voice.

“Victoria says you don’t think about these things often.”

“No. I don’t. Is that a problem? That’s why I’m here, right? Isn’t that why I’m sitting here with you?”

The priest remained silent.

“What will thinking about these things do? Find a cure? Let me die? You know, you don’t know the half of the trouble I’ve —”

Fr. Hughes bolted upwards. “Watch yourself, young man.”

“Young man? You’re kidding me, right? You —”

Before Samuel could finish, Fr. Hughes lifted the hem of his cassock to his knees. No legs. Only metallic rods that terminated at wooden blocks tucked tightly into his black shoes. “Omaha Beach.”

The sight disarmed Samuel. He sunk into the chair.

“I’m going to say something you won’t find pleasant to hear. You’ve been around longer than just about everyone, Samuel, but you’re a foolish young man. Young and stupid.”

Samuel refused eye contact.

Fr. Hughes continued. “Nobody blames you. There is a weight of the soul that comes with age, a weight you don’t have. That’s been held back from you. It isn’t your fault, but —”

“What do I do with Victoria?”

Fr. Hughes sat back down.

“What do you think you should do, Samuel?”

“I don’t know. I don’t even know her anymore. I don’t love her.”

“You don’t love her?”

“I …”

“… Love is no feeling. It’s an action, a devotion to vows and integrity. You’ve stood by her side longer than most people live. Of course you love her.”

“I … I’m sure she’s told you.”

“The infidelity?”

“What am I supposed to do? She’s eighty-one. Eighty-one. And look at me. How am I supposed to —”

“She has told me,” Fr. Hughes confirmed with a stony face. “Adultery. That’s what it is, Samuel, but it’s not out of this world, given your circumstances.”

A weight was lifted off Samuel’s chest. “Thanks.”

“Don’t thank me. I’m not excusing it. It’s pathetic and filthy. But I understand it. You never grew old with her. You’re still young. Still just … through the mysterious providence of God, still a young man.”

Silence.

“You don’t read much, do you? Victoria says —”

“What? What does Victoria say? That I sleep all day? Stare at the television set? Drink liquor by the gallon?”

“Samuel —”

“Just tell me what I do with her. Tell me what to do.”

The priest sighed. “Fine. This is exactly what you’re going to do. You will respect your marital vows. The mama’s-boy teenage philandering, the sneaking about with other women, will stop. You are going to stick by her side until she dies. You will make an attempt to see God in your life, and why He desires something from you that He has never — and I mean never — asked anybody else for. You will think about this, ponder it, and try, Samuel — try to pray about it. And, lastly, you will not seek any answers from the world for your condition. Victoria is far too old for her household to be the center of a media circus, but you know that already, from what I’ve been told.”

“… Anything else, your majesty?”

“No. I have a meeting in five minutes. If you are interested in talking, Mr. Carmichael, my door is always open to you. Always. Until then, ciao.”

Samuel stood up, fixed his shirt, and walked towards the door.

“ I don’t pray, Mr. Hughes.” Samuel opened the door, slammed it shut behind him, and disappeared down the hall, laughing and cursing to himself.