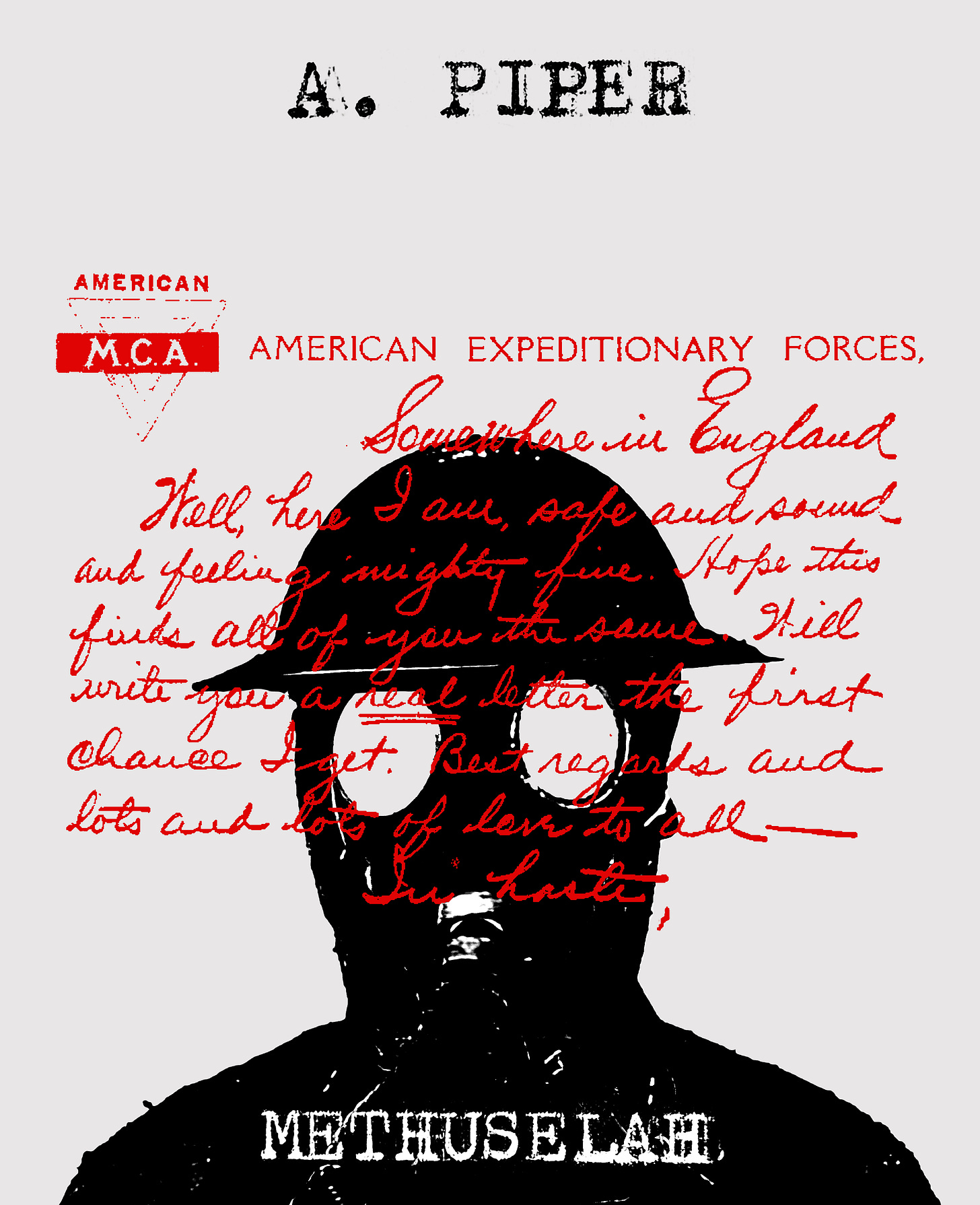

METHUSELAH - Chapter I - "Islip" - Part II

November 7th, 1918.

Sergeant Carmichael was no longer a Sergeant of the United States Army — only “Sam”. The war was finished, for the time being. The future was no longer what it used to be, but nobody wanted to hear that; the boys were home, the markets roared, and meatless meals were a ghost of the past.

The weather was perfect. Leaves crunched under his heel. Children played stickball and the sun smiled upon old men reminiscing under the shade. Samuel was dressed to the nines — a 3-piece suit and a hat hugging his head. He walked along the road, putting one foot afront the other, unlike so many of the men his age who didn’t return from Europe alive.

He was visiting Marie.

Orders were orders, and the men were ordered to fight no matter the toll on mind or body. But the fighting was over. Samuel wasn’t adjusting like he thought he would. He ate and drank the death overseas, but he relegated those sickly meals to a corner of his mind that needed no revisitation. There was no debriefing of the men in those days — no referrals by officers in the sickbay to a civilian head shrink, no access to mental health services at the VA — only the gifting of discharge papers, a pat on the back, and a hope-to-never-see-you-again. Don’t look back, young man. We won’t be there. Go on your merry way, now.

The final death in Samuel’s war was Marie. He was good at swallowing his emotions. Always was. Acted as if he never saw his mother get the brakes beaten off her by papa. Lived on as if Papa never told him that he was the last thing on anyone’s mind when his mother was, in the man’s words, getting done on the sofa like a bitch in heat. He buried Maynard in the French soil when his feet found America. Buried Dr. Turrell, Corporal Johnson. The three Italian boys from Brooklyn minced by an exploding shell. The Randazzo boys. How old were they? Doesn’t matter. Never existed. Never happened.

Pushed forward, he did, all while ignoring a heart bloated with blackness like a chow-hall grease trap.

He passed through the gate of Calvary Catholic Cemetery. Flowers in his hand and a long-lost lightness in his eyes, one would think his date with some local Jane was only minutes away.

L-5-14. Marie’s final resting place — according to his mother, under an elder maple as beautiful as could be.

He passed graves along the main path. George Townsend. Just an infant. Geraldine Schmidt. A loving mother and wife. Harry Nash. Born 1842.

F … G …

Henrietta Spalding. John McCullough III. Jeremiah Hampton.

J … K …

A wife. A serial grifter. A longshoreman. A good-for-nothing son who died in a bank robbery.

L.

Samuel turned right. The rows of graves stretched to the field’s end. Perfect rows, except where the plots were dug around a tree with a hollowed-out knothole where birds nested.

Sarah Smith. Wernher Kohler. The hated. The missed. Names of cheaters, liars. Of pugilists, bastards, the insane. A pianist, a banker, a hot-tempered knifeplayer. Names of the loud wicked and the silent good. Enough names to —

Marie Carmichael.

She was near the edge of the property, right under a tree as his mother said.

Beyond the fence, two boys ate ice-cream cones, pointing at ants scurrying about.

Samuel looked all around. Nobody here. He smelled the flowers he held — a wonderful scent, handpicked by the Spanish shopkeeper’s daughter, a tall, slender girl with ravenblack hair and coffee-colored eyes.

“Hi, Marie.” He greeted her as if she was baking something real sweet-smelling in the kitchen again, and he just walked in after a long day at the steelyard. He set the flowers onto the gravestone and sat cross-legged. Something was amiss. His rifle was missing, his helmet was gone, but an onslaught began nonetheless. The walls guarding his heart crumbled to nothing.

“It’s … been a while since we spoke.”

He paused for a while in a breeze, then smiled; tears began. “I’m here, Sis. I’m right here. I made it back home.”

A blue jay disappeared into the maple’s knothole.

“I made it. It was rough. I missed you every day, even when I didn’t. I heard …”

Smiles became sobs. “I heard you read my letter that morning. Boy, that makes me glad. That makes me real glad.”

Another blue-jay joined the first in the tree.

“You would’ve loved the Eiffel Tower. Saw it in person, before I was sent off to England. The paintings and photographs don’t compare. Europe’s something to see, when … when there’s no fighting and nothing is destroyed. Had a real swell time when the shooting stopped. You would’ve loved it, sis … hey, I brought you something.”

Samuel reached into the pocket of his coat. Stuffed inside was a folded silk scarf, handwoven in Paris, dyed a deep purple. The young merchant, a certain Mathilde with waist-length hair and a glass eye, practically gave it to him for free. He set it at the grave and sobbed, his face finding his hands.

He could forget all that ate away at him, all that stole his peace from across the Atlantic, but he could never forget Marie, his sister. His best friend. “I’m sorry I wasn’t there, Marie. I’m sorry. I’m sorry.”

… Apology after apology. Blame taken, blame shed. Her big brother Samuel wasn’t there for her, but he didn’t start the war. He didn’t kill Maynard. Who did? Why? Didn’t matter — not to Samuel, at least in that very moment. No, not yet. His chest emptied of pain and guilt with the tears that fell at each quaking sob. Time passed. The sun marched across the sky and the tears stopped. Marie was gone forever. He made peace with the reaper and watched the blue jays enter and leave the knothole. Wide and golden the maple’s leaves were. The graveyard was lively, as Marie had once been. His back ached and he laid down flat for a while, staring at the sky and swimming in its blue, and after some time, Samuel turned on his side and fell asleep. The sun was setting right as he woke up. It was the best sleep he had in a while.

He wanted to say goodbye, but only goodnight left his lips. As he turned to leave, he looked once more at the purple scarf, then at the maple tree. A grand idea entered his head. He removed his jacket and shoes. Tucking the scarf into his pocket, he climbed the maple, branch after branch. He neared the top. Scooting out to the middle of a branch that hung over Marie’s plot, he tied the scarf around it. It was a tight knot, a kind that Sergeant Burroughs, a former sailor, taught him. Samuel was confident it wasn’t going anywhere anytime soon, and there it’d stay, a ribbon of color swaying in the wind, for months thereafter.

January 18th, 2010.

Barack Obama landed in Boston the day before to show support for Democratic candidate Martha Coakley who ran to fill the seat of the late Senator Edward M. Kennedy. Samuel couldn’t connect. He switched the television off after a few minutes. At least thirty years old, it whispered into a room haunted by his reflection on the screen.

On the windowsill sat flowers in a vase. One of the nurses at the hospital — he forgot her name — was kind enough to send them. Tied around one of the flower stems was a strand of twine looped through a hole punched in a greeting card. Nothing was written inside. He didn’t blame her. Couldn’t. She didn’t know him. Wouldn’t want to, he figured.

The television’s emptiness robbed him of gaze and drew him in at gunpoint. End of the line. A perfect mirror. The glare from openings in the curtains evaporated into a diffuse silicon mist, and in the darkness, he saw only his jagged form rotting on the couch. The show was over and the electricity was cut but he still stuck around, sitting, waiting, forever.

“Samuel? Sweetheart? It’s noon. Don’t you have work?”

“No, sweet pea. Not today.”

“When, then?”

“Never.”

“Don’t be silly. You can’t sit still, Mr. Workaholic.”

“I’ll just sit here until eternity. What’s eternity like, sweet pea?”

No answer. Eternity is nothing, Samuel whispered back into the screen. A long nap. A bottomless canyon. Falling, falling, forever. Stuck. Not asleep, not awake.

When time doesn’t end, time doesn’t exist. No dismemberment of infinity. Division by zero breaks the rules. He fought with the screen’s reflection for minutes that became hours, hours that were epochs, but still only seconds long. An entire life was lived in thoughts thrown across the room. He couldn’t bear it. There was no release. No finality to cognition. He couldn’t sleep. He couldn’t eat, except when he could. Loss of appetite and a desire to eat were one in the same. Anger and terror and joy and curiosity strangled him. Separately, and simultaneously. No escape. Madness is being all at once and Samuel was mad as a hatter, for existence is divided into states of being, and intervals of eternity are eternities. When time doesn’t end, time doesn’t exist. No dismemberment of infinity. Division by zero breaks the rules. He fought with the screen’s reflection for minutes that became hours, hours defined as both seconds and eons and —

7:19 PM. Fire engines roared down Main Street, eastbound. Their screams broke through the cloud oppressing Samuel’s mind. Respite. Bodies in motion stay in motion, and sitting still just wasn’t right anymore. Maybe something will happen. His hope for decades. Drive, drive. That was the first instinct. Montauk Highway gave no answers, nonetheless. Neither did the Southern State Parkway or any of its citrine lamps along the bends but he had to try. Shoes found his feet and a leather jacket hugged his torso. He locked up the house and entered his car.

He drove along Montauk Highway westbound, past the hospital where Victoria died and the church where the funeral mass was held. Nothing. Empty air. He turned onto the exit for the Sagtikos Parkway, northbound. Light after light, exit after exit. Disappointment codified in monotony, the fate of a fable unsolved. For Bethpage State Parkway, northbound, he exited, turning the high beams on. Raindrops tapped the windshield. The highway was dark. Time to disappear. Don’t do it, Samuel. Don’t do it. He jerked the steering wheel to his left and careened into the embankment, sending glass into his eyes and jagged metal through his chest, but only in his mind. Wouldn’t work. It never did. Soon, the roundabout. He turned onto it and exited west. Drove for three minutes. Three hours, eons, centuries. Three eternities of lonely sighs and leftover casseroles and dead friends. Hopped on Route 135, northbound. Still, nothing. Northern State Parkway, westbound. A car was pulled over near the first overpass — a car with a finite battery and a radio that always had the correct time. Fortunate. Exited northbound to Glen Cove Road, turned left onto Northern Boulevard, towards Queens. Halfway through Manhasset and he was driving in Koreatown and soon, Chinatown. The nightlife was vibrant. He passed through Flushing. New York City was in the distance. The steel sentinels saw him from over there, knew his secret, and laughed silently. They beckoned him to draw near. He drove closer. Autopilot. No answers in the night. No punctuation of the endless. The noodleshops and bars and late-night Chinese supermarkets gave nothing. They’d be gone before him. When? One hundred years, two hundred, several thousand. Didn’t matter. Passed the stadium. Before long, he entered the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. He rode it, passing Manhattan sideways. The tower’d behemoth tracked his movement southbound. Dazzling lights, the metropolis had. Filth, too. Corrupt like a vinyl record warped from overuse. South. Past Staten Island, under the Verrazzano Bridge, past the long-gone Nellie Bly Park, past Coney Island. Onto the Belt Parkway, eastbound. Past JFK Airport. No traffic on the Belt near the airport. Odd. The lights of Brooklyn gave the sky a frigid glow. Daydreams, nightdreams, nods behind the wheel. Back onto the Southern State Parkway. Déjà vu. Ouroboros. Oppressive recurrence. No answers. Questions begging to be abandoned in a coffin, coins on the eyes, the inquisitor laid to rest. The long trip back to square one. More raindrops on the windshield. A terrifying scenario: What happens first? My memories finally putrefy as I walk dead on my feet, or the rain washes New York City away? Terror. Time passed. Much time passed. Not much at all. The same exit, 39 South. Back to Montauk Highway. Back to Main Street. Back to Vermillion Lane. Back to the house. Back to the bathroom, the bedroom, bed, again, again, again, a fist through the wall, a stomach in knots, tears, ghosts, life lost between cracks in a sidewalk that leads nowhere.

November 7th, 1918.

A short walk away from the cemetery, on Browns Hill Road, a sorry-looking diner came into view. Wooden shingles hung off the roof and a few of the windows were cracked. It wasn’t like others he had seen — no stainless-steel siding. Hungry, he stepped inside against his better judgment.

The inside fared much better. The floor tiles were new and a radio blared in the corner. A few gentlemen were sitting at the counter, talking away, smoking cigarettes, waiting on or finishing their food. Samuel hung his hat and coat on a hook near the entrance and sat at the bar. Perusing the overhead menu, he ordered a cold roast beef and horseradish sandwich, and a vanilla milkshake.

“Carmichael.”

Samuel looked over to his right and found a well-dressed man, two stools over, staring him down.

“Carmichael, right? … Say, it is. I can’t believe it. Is that you?”

He couldn’t figure out who the man was until he removed his glasses and hat. Legrand.

“… Legrand. Wow.” The two men rose from their stools and shook hands.

“How long ‘s it been, Carmichael? I haven’t seen you since … since, what? Eighteen, in February.”

“Yeah, that’s right. That’s right. Look at you, kid. All grown up.”

They both laughed a clean, pleasant laugh.

“Move your seat over here, will ya?” Samuel nodded and moved the stool.

Twilight fell as the two passed the hours catching up. Samuel was dressed for town but still carried something foul in his face. Legrand never went to Europe — or so it seemed, at least. He’d been in the trenches and survived, somehow, some of the goriest battles of the war, including multiple gas-shellings. No surprise. His mask had no faults. That was all behind him, though. All of it. There was a lightness in his face. He never intended to keep contact with the guys from the front, but seeing Sergeant Carmichael in Pittsburgh was pleasant enough. Chester Legrand was working for a freight-forwarder in New York City and was only passing through Pittsburgh to see a young lady he fancied. The two of them were to be married in a week, and after that was an indefinite honeymoon in Paris.

“Paris, huh? What’s there?”

“What’s there, sarge? It’s the ritz of Europe, that’s what. Where the culture is.”

“The … culture?”

“Yeah. Sure.”

“… Since when did you ever give a damn about that?”

“About what?”

“… Culture,” said Samuel, cringing.

“Well, that’s not it, sarge, it’s —”

“Samuel. Samuel is fine —”

“— it’s also where work is. The company wants me in the Paris office.”

Samuel raised his eyebrows and sipped his coke. “If that’s what you want.”

“You don’t say it’s a bad move?”

“I want nothing to do with Europe, Legrand. Nothing. Those Huns —”

“The Huns? Please, Carmichael. They’ve had the snot beaten out of them. They’re done. I saw my share of —”

“You forgot.”

“I forgot?”

“Sure did,” Samuel shot back. “It’s only been a bit more than a year, and you’ve forgotten what — ”

“Easy there, sarge. Don’t tell me I’ve forgotten.” Legrand moved in closer to Samuel and maintained an intense stare. “Having trouble at night? Can’t sleep?”

Defeated, Samuel looked away. He disappeared behind a clock on the wall. “… That’s right.”

“Same for me. Don’t you tell me I forgot. I almost died on that hill. Almost … you sure you’re alright, sarge?”

“I’m doing fine, and —”

“Let it go, Sam. It’s behind us.” He finished off the coke and set it hard upon the counter. “Especially the Huns … nothing’s left in them.”

The sparring continued as both defended their positions with tired determination of years past. Then, armistice. Minutes passed in silence. The two searched for something else to say but the meeting’s termination was overdue. Legrand rose from the stool and peeled his jacket and hat off the hook by the doorway. There were droplets of tomato soup still on his right hand. It was better for him to just leave. He pushed the door half-open. Regret caught him red-handed and he turned around say farewell.

“Carmichael.”

“Legrand.”

“Take care of yourself.”

Samuel remained seated. He turned, looking over his shoulder, and shook Legrand’s hand.

“You as well, Legrand. Enjoy yourself in Paris.”

To disappear was daring, but, after all, Gordon had done it.

His house by the road, with white paint over aluminum siding and a gazebo in the backyard, could’ve been left to the birds of prey, the bank-vultures. It was an idea. Nice cut of property. The lenders wouldn’t let it fall apart. When Gordon rode the Long Island wind, carried away with the scent of honeysuckle and cut grass, the place was foreclosed not two months later. I could do that, Samuel thought.

Rationality prevailed, nonetheless. The Carmichael residence, 9 Vermillion Lane, a two-story cape cod, was estimated at $390,000. His total assets — savings, investment accounts, the like — just over a million two-hundred. That number didn’t include the Social Security payout he’d never think to touch. He couldn’t bear the thought, in his own antique way.

Anthony Stanco, Esq.The nameplate’s bronzing was faded. After the fire, Anthony Stanco’s legal practice withered; he maintained former clients but refused new clientele. He’d lost his ability to hear, speak, and not be treated like a charity case, so to most, the early retirement was understandable. Yet he made all the time he could for Samuel Carmichael; the man paid well, and his condition — which Stanco would’ve doubted entirely had it not been for Samuel’s face refusing to age over their fifteen-year relationship — made the man entertaining, even if what Victoria relayed about him was a fantastic hoax. For this one client alone, it was worth keeping the dingy office at the 500 Building in West Babylon.

Samuel knocked on the door. A young man with glasses, red hair, and freckles opened the door.

“Mr. Carmichael? Come in,” he said.

Samuel stepped past him, glaring. He walked right into Anthony’s office, made eye contact, shook his hand, and pointed towards the young man as he followed Samuel in.

“New guy?”

Anthony nodded.

“Can I trust him?”

“I’m Thomas. Nice to meet you,” the young man said, sitting in a chair beside Anthony, who was signing rapidly with his hands.

“Buried under a mountain of non-disclosure agreements,” said Anthony through Thomas. “Don’t worry.”

“I’m leaving town. I’m done here. Selling the house. I think the car.”

“Victoria too?”

“Excuse me?”

“I meant if she’s leaving town too, dummy. Did you really think –”

“She’s dead.”

Anthony diverted his eyes to the floor and shook his head. “I’m sorry, Samuel. I’m so sorry. When?”

“Two years ago. She was a week away from a hundred and eight. Or nine. Whatever. Don’t be sorry.”

Solemnly, Anthony nodded. “It’s been that long since I saw you last.”

“Sure.”

“Did it happen at home?”

“What?”

“Her passing.”

“No. The hospital.”

“You two always mentioned it happening at home.”

“She was in serious pain. Couldn’t get the pain killers without a doctor … last minute decision.”

“I see.”

“… You’re looking older, Stanco. Anyways, I need everything to be done through you — the sales, the transactions, the paperwork, everything.”

“Liquidating everything?”

“Yeah.”

“You alright?”

“Yeah.”

“You sure?”

“Yeah.”

Anthony knew he wasn’t.

“OK. Just so you know — Glenn went off to college. He isn’t around anymore to translate for me, so I’ve been keeping this ginger idiot around. No, I’m only kidding. He’s a great kid. But, he needs to be compensated fairly, so my rates are a little higher than they were two years ago.”

“Sure. That’s not a problem.”

Anthony nodded. “I’ll have Thomas deliver the paperwork to your house. I’ll circle everything you need to sign. There may be more depending on what you’re selling and … what the other parties need. So watch out for my calls, OK? It’ll be Thomas calling. Your phone number is the same?”

“Yeah.” Samuel’s eyes tracked a beetle crawling on the window behind Anthony. He cleared his throat. “How are you doing?”

The burnt man faked a smile. “You’re looking at it.”

“Glenn’s gone off to college, you said?”

“Yes.”

“Where?”

“Boulder.”

“Arizona?”

“Yeah. It’s good for him. He needs to be far away for a while.”

“It’ll be good for him.”

“It’ll be good for you, too. Leave this damned island. You’ve been here a while. You need a change.”

Samuel gulped.

At that, he stood up, extended his arm for a handshake, and left the office.

Casting out Victoria’s belongings proved to be a reminder of the final destination he lost the invitation to. The last of her things — unimportant articles of clothing — saw the curbside on a day with thunderstorms and light hail. Samuel cursed. The house sat empty, save for a mattress on the floor and belongings packed into suitcases. He’d be gone the next morning and the newlyweds would arrive the day after. What was their names? Amanda? Jerry, or James? He liked the young woman. She was witty. Nice legs. Couldn’t stand the husband. Snobbish. A stubby trust-fund brat with two days of lunch smeared on his blazer. Stunk to the high heavens like sweat and curry. But the woman — Samuel saw life in her smile. A few more smiles, a morning swim in the pool of her eyes, and he cut around thirty grand from the asking price. The agent was livid.

“… don’t tell me what to do, Juan.”

“I … I apologize, Mr. Carmichael, but you need to know this makes a ton of paperwork for the both of us, and —”

“Well, there’s plenty of real estate companies in town. Let me know if there’s any issues going forward and I’ll take the business elsewhere.”

Juan capitulated. He was a weak man. So was Samuel. A flashy smile robbed him blind. He was a sucker for beautiful women. No two ways about it.

All the paperwork was finalized on February 18th, 2010. The bars on main street were glowing with life when Samuel walked by at a quarter to six — happy hour. A distant part of him wanted to drink beer and put his hand on the small of a young lady’s back.

“Oh — uh, pardon me,” said Samuel, his brow raised with apology. A man no older than twenty-five left a bar and walked to the curb. Samuel, lost in thought, bumped shoulders with him.

“No worries,” the man replied. His thin frame stepped beside a motorcycle, a black-painted Honda cruiser with a beaten-up saddlebag. The helmet cradled in his right arm was black, too, with a red mohawk stitched down the center. Mounting the bike, he saw Samuel — unexpectedly captivated — staring at it.

“You ride?”

“No,” Samuel said.

“Oh.”

“It’s a nice bike.”

“Thanks. It’s the only thing I’ve ever ridden, really. Never had a car. She’s old, but … it’s good, and I don’t like the Harleys anyway, like a lot of these old guys riding up and down the street to the highway. There must be a bike show today close by.” He dismounted and stretched out his arm. “I’m Henry.” The helmet’s chinstraps flailed in a gust of wind.

“Samuel.” The two shook hands shyly. “Are they trouble?”

“Trouble?”

“To ride,” said Samuel.

“Nah, it’s like anything, really. Once you get the hang of it, it’s second nature. But … you have to make yourself seen. That’s where the problems are,” Henry said, eyeing the growing traffic on Main Street. “Half the time, they don’t see you, and that’s when they fuckin’ smack right into you. Not like when riding a car. People see you most of the time, I guess.”

“I could only imagine.”

“Mhm.”

“I’ve driven cars my whole life,” Samuel said. “Some pickup trucks, too.”

“Well, riding a bike is different. Definitely different. But not completely. Different mindset, but you should be good. You’re still young. It’ll be second nature once you get the hang of it.”

“I reckon.”

Henry cocked his head in confusion.

“… Yeah, you’re right,” said Samuel. “How much did you pay for it?”

“Pssh. Four-kay. Not much at all. Knew the guy, but …” Henry glanced at his phone and gestured at the street. “Gotta go. Nice to meet you, Sam.”

“Yeah. You too.”

“See you around.”

The ignition was flipped. A warm tremble radiated along the curb. It sped down the street, and, turning left, disappeared from view.

November 8th, 1918.

“Well, Ma ... I don’t know.”

“What isn’t there to know?”

“A woman like her has a man. I just know it.”

“Don’t be foolish, Sam. You don’t know that. How could you?”

Samuel lifted the teacup, delicate and painted with scenes from the Low Countries, to his mouth. Sip. “I told her about Marie.”

“... Did you, now?”

“She asked about the flowers, about who they were for.”

His mother’s brow grew heavy. She lowered her gaze to the table. An ant scurried by. She tried to utter something, but it trailed off into silence.

“I didn’t tell her, Ma.”

“... Oh?”

“No.”

A frown haunted her face.

“She said,” Samuel continued, “’I hope she’ll like the daisies.’ I told her she would … didn’t see the use of telling her.”

“Well,” began his mother in between sips of tea, “What’s her name?”

“I don’t know … I don’t know.”

For a while, his mother was silent. She ventured to a place far beyond the old house, a place where daisies of every color blanketed the ground all year long. Marie, of course, was there with her, humming to herself and sticking daisies in her hair.

“Well,” his mother continued, “You ought to tell that young lady the truth. I didn’t raise up a liar.”

“I didn’t really —”

“And ask for her name. And give her flowers.”

Samuel glanced at the daily issue of The Pittsburgh Post.

FRENCH TROOPS FIX TO INVADE GERMANY IF TERMS ARE DEFIED — Activity of Military Near Border Shows Preparation.

“Maybe, Ma,” Samuel uttered under his breath, “Maybe.”

November 11th, 1918.

There she was. Beautiful, but more than he remembered. Her delicate hands, nailed painted passion-red, flicked around a potted plant with unruly shoots of green. Snip. Snip. Her black hair fell around a heart-shaped face with a pointed chin, and stopped just at her waist. Skinny woman. But shapely. Lovely. Her eyes darted around the shop, searching for the eyes that searched for hers, and they found the man’s through the window of Allegheny Arrangements, Established 1901.

She remembered him, that harrowed sergeant from the war — those gray eyes, those wide shoulders, the gravelly voice that smoothed her edge, his —

He pushed open the door and entered. The young florist pretended the man wasn’t there; young and passionate, indeed, but Victoria never gave herself to passion, and the customer who entered at that moment made her nervous, self-conscious. She despised it.

Samuel stepped towards the counter. “Hello.”

His reservation surprised her. “Hello,” she replied, letting a raised brow and sublime smile speak for her.

“I was here last week.” Samuel cleared his throat, which, to him, sounded a hundred times louder than it really was.

“You were. I remember you.”

“Oh … very good.”

“White daisies.”

“Hmm?”

“You purchased the white daisies, correct?”

“That’s right … white daisies, for —”

“For your sister.” She flashed a smile yet wider at the man who seemed to be sweating from his temples.

“Well … yes. You know, I wanted to say, uh, that —”

Interrupting his confession was a motorbike roaring down Mercie Street. The whole city seemed to stop and watch for a second or two.

“Gruesome things. They make such an awful racket. What were you saying?”

“Well … I was saying to you that I’d like to apologize.”

“… What? For what?”

“Well, the flowers — they were for —”

“Your sister,” Victoria cut in.

“Right. I said she’d love them.”

“You did.”

“That was a lie.”

She stared at the sergeant, confused and wondering if she should be scared.

“… Pardon?”

“While I was … away, in France — the war — my sister …” A ball formed in his throat. Bombs and bullets didn’t get you, but a gal in a nursery does?

“…”

“Well, she died.”

Victoria was upset with the relief she felt, a relief from knowing he wasn’t a madman about to kill her, or worse — surprising herself again — a married man. “I’m sorry.”

“The flowers were for the … for where she’s buried. Not far from here.”

“Well … I’d imagine as much.”

Their smiles met, his tinged with more sorrow than hers.

“I’ve had my say.”

“I’m sorry. I am. She’s up the street, you said? At Calvary Cemetery?”

“That’s right.”

“What was her name?”

“Marie. Marie Carmichael.”

“Married?

“No … unfortunately, no.”

She nodded her head. “It’s nice to meet you, Mr. Carmichael.”

“Oh, it’s Samuel. The, uh, pleasure is mine. And you are …”

“Victoria. Victoria Castillo.”

He nodded shyly, turned on his heel, and walked out into the street.

Strange man, Victoria thought. As handsome as could be, but strange.

I hope he returns.

Later that night, Samuel slinked through the front door. What the hell kind of talking was that, he thought to himself. What did I even say to her? He couldn’t remember. A shepherd’s pie baking in the oven roused his hunger, but he didn’t want to eat. Disappointment fed him enough. It distended his stomach. He crept past the kitchen. His mother glanced up from the Reader’s Digest in her hands and called out to her son.

“Samuel?”

No response.

“Samuel? What happened, dear?”

Silence.

“Oh, that boy,” she admitted softly to herself. “Lord have mercy on him. Show him the Way.”

Troubled sleep summoned a nightmare, the same one as always with little variation. Shouts, gunfire, pandemonium, Maynard dying under a red sky. Samuel looked upwards only to drench his face with blood raining from the rusty clouds, and looking back down, the choking Maynard was a bleached skeleton, grinning in his tortured slumber. Scream, Samuel couldn’t. Nor could he breathe. He suffocated alone, his only company the mountain of skulls and bones he trod upon.

May 19th, 2010.

Omaha.

Pittsburgh was dead. Couldn’t go there. Couldn’t stand to see the skyline or the stadium from the highway or the suburbs along the Ohio River that, once upon a time, gave quietude to friends and family long since gone. Calvary Cemetery had his mother and Marie, but the tombstones grew worn and the neighborhood changed, and the whole region was no longer home.

Sergeant Petrenko — Was he a sergeant? — Samuel couldn’t remember. He was from Omaha. Cut down by a machine gun nested on a pretty little hill with daisies growing on the side. Ukrainian fellow. His family owned a slaughterhouse on the southside. Was sitting pretty with a nice chunk of change in his pocket and the fool signed up to be mince-meat on a foreign field. Not a fool, Samuel thought, but the others did.

Omaha — he and Victoria passed right through in ’61 on their way to the West Coast. The rain poured and the two couldn’t see anything of note from the interstate. Samuel was tired — he craned his neck left and right to catch any kind of building taller than a telephone booth. He paid little attention to the road and smacked into the bumper of the Volkswagen bus riding ahead, its owner most certainly distracted by the drab landscape in the same way Samuel was. The two cars pulled over and the driver, a small, skinny man named Michael, was forgiving. Insurance information was exchanged when the police arrived, and all were on their way again.

Sam, let me dr—

No. I’m fine.

It’s straight driving, Sam, I can —

Victoria, just shut up, OK? Just … just be quiet.

… OK, Sam.

He remembered her tears, her silent sobbing, his unwillingness to even look at her, and, of course, the other woman he wished was in the passenger seat, flashing a lively smile through lips colored red like the blood of his still-young heart.

May 25th, 2010. He bode his time for days at a Marriot Hotel in Farmingdale. Bode his time. More accurate: he was paralyzed for days at a Marriot Hotel in Farmingdale. Samuel Carmichael was a scared man. Behind the intense brow and calloused knuckles and eyes that saw the killing fields swallow men whole was a fear that hugged his spine and never let go, a monster yet unnamed. Sometimes it’d loosen its grip and disappear for a while, letting him walk or talk on the day it decided to give false hope, but it slept under his bed and danced on the dinner table and cackled behind the curtains of the home Victoria kept. When it reared its head, he couldn’t move about or get the groceries, or get Victoria to her appointments on time, appointments where Dr. Halversen, after more than thirty years of practicing medicine, still didn’t have the sense to tell an old woman that her condition was age, and that she was simply dying, and that her rosary beads wouldn’t stop the clock as it did for her ‘son’ Samuel.

Four boxes, two suitcases, a gym bag, the flesh on his bones — it was all that he owned. Samuel looked down at the black pickup he purchased through Mr. Stanco about thirty times a day from the hotel room window. Tomorrow morning. Tomorrow morning. Or, I’ll just drive. I’ll just go west.

Go west, young man. Ain’t a thing for you here.

He blinked. Once, twice. Everything was a blur. His mind was slipping. He knew that. Tried to cry for days. Nothing came forth.

He found himself at the hotel’s checkout desk. Was everything fine up there? Come back soon. You have all the time in the world, Mr. Carmichael, don’t you? Nothing but time to plan our funerals, to shovel dirt atop the coffins of the world.

Goodbye, Mr. Carmichael. We’ll all be dead a hundred years when your tomorrow arrives.

Fare thee well.

A favor: If you genuinely enjoy the read so far, share it with as many people as you can. Thank you!